I've been thinking a lot about the Holocaust and what it means to be Jewish as Israel, the land where Jews traveled for safety after suffering a world-shattering genocide, is now committing a heinous genocide of its own.

This is purely fiction, but the spur was my Hungarian stepfather, himself a survivor.

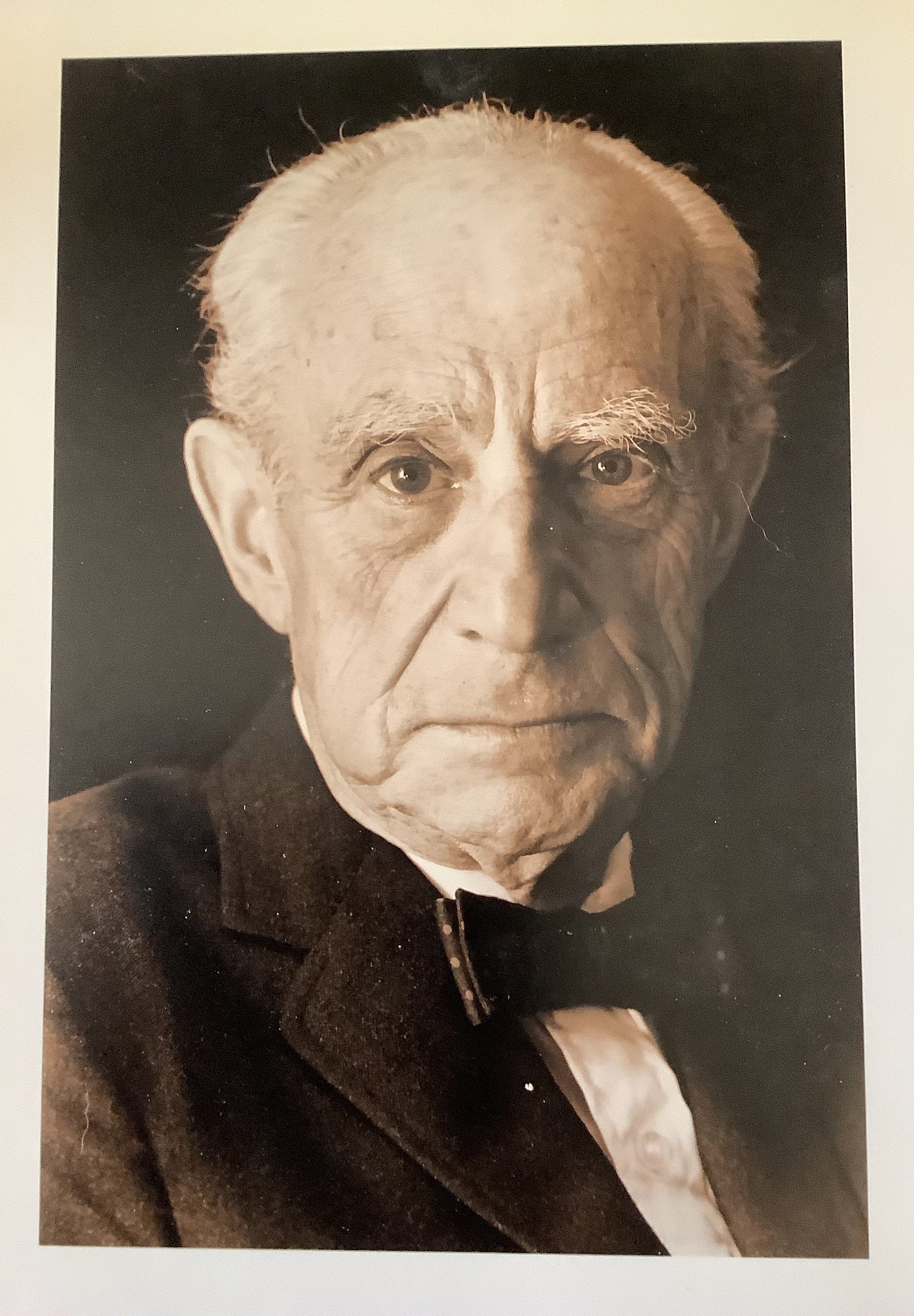

Dr. Edward Erdelyi, my stepfather.

****

I have been sitting here for a long time on the bed next to his body. I should call someone to come and take him away, but I’m not sure who. A funeral home? The police? He’s hard and cold, and he doesn’t look like himself, or like anyone really any more. The eyelids bulge over his closed eyes, his nose is sharp, his skin yellow, his mouth wide open. He didn’t struggle when death came sometime in the night, probably courtesy of his deficient heart. The bedclothes are smooth over his chest, and his open hands rest on it palms down, as if someone had carefully placed them there, first one, then the other. That must be why I didn’t feel the spirit leaving him in the middle of the night, though I could tell as soon as I awoke that he was dead, and had been for some time.

What I feel is nothing. Nothing at all. I think about touching him, sliding my hand under one of his to see if it makes me feel anything, but I don’t move. He’s gone. Loud, excitable, argumentative George Kovacs is gone, flotsam waiting to be hauled away. Part of me has wanted this for a long time. Standing in the shower, driving to the store, I’d fantasize about life without George, think about how I’d throw out his things and rearrange the house, how I’d spend our money. And I’d wonder, now that I was too old to get a job and had spent decades helping him achieve success, was there enough money saved for me to live out my life alone and in comfort?

I shift a little and his shoulder bumps against my back. It’s like a stone; it makes me gasp. There was a time when I liked touching him, and having him touch me. That rigid shape behind me is the man who gave me my first orgasm. I remember him on the night of our marriage driving deeper and deeper into me, ferocious and unrelenting. I remember feeling angry and cold and then spiraling suddenly out and out, darker and darker, deep into fathomless space.

I knew the source of his ferocity, or thought I did. He wasn’t always George. He was born Gyorgy in Hungary, and when he was fourteen, they put him in Auschwitz-Birkenau. In the early years of our marriage, I read everything I could find about the concentration camps, pored over the images in old photographs—men in dark hats and coats with yellow stars on their arms, children looking at the camera, pajama’d skeletons behind barbed wire, chimneys pouring smoke into empty gray skies. But he would never tell me what he had experienced. It was over, he said. In the past. But it wasn’t over. It was in his every breath and gesture, behind his closed eyelids while he slept. Auschwitz was the reason he wanted to maintain a bright, modern American home, to forget his European languages: Hungarian, Czech, German, French, Italian. It was probably the reason he married me.

I met him in college. I was never a serious student, so I didn’t know how to react when Gyorgy Kovacs, an assistant professor ten years older than me asked me out. I had no idea what to think about him, this short, voluble, big-eared man who took me to restaurants with white tablecloths, asked what I was reading and began issuing directives about how to improve my grades. I found his accent exotic—though I couldn’t have picked out Hungary on a map if you’d asked me—and I couldn’t help noticing the deference with which his colleagues treated him, and the mixture of mockery and awe he inspired in his graduate students.

Having pressured me to finish my degree and married me, he announced that he didn’t want me to work. My job was to keep the house clean and entertain his colleagues. I learned to cook, but he never said anything about the meals I made. He did reminisce periodically about the food his mother had prepared for him: things with cabbage and potatoes, dumplings, cherry strudel and chestnut puree. One day I found an interview with a Czech woman in the food section of the paper, along with a couple of her recipes. I went running to the store for paprika—I’d never used it before, but they had some. I was excited. It was still early in our marriage, and I wanted to please him. I played the radio loud in the kitchen as I cut up a beefy tomato, an onion, a green pepper, tipped everything into a big saucepan, added chicken pieces, and scattered the bright red paprika over them.

He bustled in promptly at six and went into the study to set down his briefcase. Then he came out grumbling about something his department chair had said. I portioned out the chicken and set the plates on the table.

He took a look at his plate. “What’s this?”

“Chicken paprikash. It’s a Czech recipe from the paper.”

He nodded and took a mouthful. I waited. “This color. Why is it so pink?”

“I think that’s the sour cream.”

“Sour cream? My mother didn’t put in sour cream. This chicken must have a thousand calories.”

That’s all he said, but he continued to eat nonetheless, in big, noisy mouthfuls, reading a scientific paper and splattering it with pinkish gravy. When he was done, he gave my forehead a perfunctory kiss and went into his study. I stayed at the table.

It hadn’t occurred to George that I had gone to any special trouble for him. It was as if a piece of his brain was missing, the piece that allows us to empathize with other people, to comprehend the universal system of words, smiles, and gestures with which ordinary humans communicate with each other. Looking at the gnawed chicken bones on his greasy plate, I thought about the way he ate his half grapefruit every morning, attacking it with a narrow, serrated spoon, digging and scraping until there was nothing left but rind, and then upending the grapefruit half and squeezing until it yielded every trace of flesh and flavor to him, drop by drop.

I never understood what he’d been through in Europe because he wouldn’t tell me, and as the years passed, I cared less and less. Auschwitz was transformed from a concept too huge and hideous to grasp into something ordinary, a long-ago event that gave George an unfair advantage in the long, bitter war of our marriage. How can you argue about anything, from the color of the carpet to your yearning for a baby with a man who has a number tattooed on his skin?

Oh, yes, I did yearn for a child, and at the beginning it seemed he wanted one too. But time went by; year after year, I asked him about it, and year after year, he said, Not now. Not yet. And then, five years into our marriage, he said flatly he didn’t want children. He’d decided that he would never father a child when he was fourteen, in Auschwitz, when he heard them burning the babies at night.

Burning the babies?

He shook his head and walked out of the room.

I became obsessed with babies. They seemed to be everywhere I went. I saw mothers nuzzling their newborns at the supermarket checkout stands, children swinging and seesawing on the local playground. One evening, we were on our way to a dinner at the home of George’s department head. He was in a jovial mood as the car slid along the quiet, suburban streets.

“If we have a baby,” I said.

In profile, his face seemed to tighten.

I couldn’t stop. If we had a baby, I said, I’d make sure he wasn’t inconvenienced; I’d take care of it, keep the baby out of his study and the house quiet. His research wouldn’t suffer. George said something half-hearted about money, the cost of food, college; I responded that a lot of his colleagues had children; suddenly he slammed his hand down on the side of the wheel and the car swerved violently. “No. I will not have children. I will not have a child in my house." Never. He yanked the car straight and repeated, "No."

I began to cry. We were drawing up outside his chairman’s house. I couldn’t stop the tears, and my nose was starting to run copiously. He handed me his handkerchief without saying anything. I blew my nose and mopped at my face. “Are you ready to go in?” he said. I answered yes and started to cry again.

We kept driving round the block. Every time I thought I had managed to compose myself, the tears returned. I was furious, grief-stricken, embarrassed, and I couldn’t even tell which emotion predominated. I knew I had to pull myself together so we could go in to the dinner, but I was sinking into a pit of grief so dark and deep I thought I would drown in it. Round and round and round the block we went, while I choked on words I couldn’t shape or speak.

I turn to look at him now, the source of this ancient grief, Gyorgyi Kovacs who escaped his murderers at the age of fourteen and succumbed to the weakness of his heart at the age of seventy-five. Do you remember? I ask him silently. His mouth is a cavern, open, vast and dark.

After that evening, I could barely tolerate his love-making. What I’d once seen as passion I now saw as nothing but greed. His face as he pistoned in and out of me was the greedy, self-absorbed face of a suckling baby, lost in sensation, lost in itself.

I didn’t give up entirely. I asked him to come with me to a marriage counselor. He didn’t see the reason, he thought we were doing fine, but he agreed.

She was a large, plain woman with a long, gray braid who worked in a room that looked like a cozy, grown-up nursery—everything in primary colors, lots of home-made ornaments and knickknacks, a big, squishy beanbag on the floor. The first thing she suggested was that we each write up a list of the things we liked or loved about the other for our next session.

It seemed dumb, but I was desperate. One evening when he was at a department meeting, I sat down at the table with a pad of paper and a ballpoint pen. I wrote: I love ... I stared at the blank page. I got up, went into the kitchen and stacked the dishes in the dishwasher. Dried my hands. Came back. What did I like about him? There must be something. Finally, I wrote, He’s a brilliant physicist.

Was that really something I loved? I didn’t know enough about physics to appreciate just what his brilliance might consist of, but there was something fascinating about the idea that a mind that struck me as so miserly was on some level vast and expansive. I thought of George’s increasingly domed forehead, and the jokes he made about getting more highbrow by the year. What patterns formed behind that dome? Were they intricate and beautiful? And what memories? What had he said? They burned the children. The sentence on the pad blurred suddenly. What was the matter with me? How could I expect tenderness and understanding from a man who had suffered so much?

It was if he was a book I was struggling to read, the book of old Europe, blood-soaked, pock-marked, splintered and bombed—centuries of culture, music, philosophy, politics and art tainted and darkened. The patches of words that remained were blurred and formless, fading into darkness at the edges and, as I tried to make them out, he defended them with an army of sharp blades.

I got sentimental, I guess. I thought if I showed him enough love I could reach back in time and rescue that fourteen-year-old boy, that skinny-legged, big-eared boy, Gyorgy Kovacs. I began writing fast. I love his brilliant mind. I love his laugh and would love to hear it more often. I love the way he can charm his colleagues. I love his devotion to his students, the way he treats them as if they were his sons. That stopped me for a moment. I forced myself to keep writing: I love the way he used to touch me in the beginning.

I’ve been sitting here on this bed a long time. Hours, perhaps. I really should call someone.

On our next visit to the marriage counselor, I read my list, struggling to keep my voice even. He didn’t look at me while I read.

“George,” she said, “what do you think about what your wife has written?”

He nodded. “It’s nice.”

“Can you say a bit more?”

“Why is she always talking about the war? The war is over.”

“She isn’t talking about the war. She’s talking about what she loves about you.”

“Yes. Good. Thank you. It’s nice.”

The therapist looked puzzled. I stared at a woolly, red-and-green god’s eye dangling from a string in the corner. Finally, “How about your list?” she said to George.

He hadn’t had time to make one, he said, pinching his mouth.

She was exasperated, but she wasn’t giving up. “Why don’t we give you a minute, and you can think of a couple of things now.”

He gave an elaborate sigh, pulled his fountain pen from his breast pocket, made a show of looking for paper. She handed him a pad. He sighed again, and began to write. For several minutes there was nothing in that colorful, childish room besides the scratching of his nib, long pauses, more elaborate sighs. Apparently it was very difficult for him to think of anything he loved about me. Finally, he signaled that he was ready, the counselor nodded, and he read: She supports me in my work. She learned how to iron my shirts exactly the way I like them.

It was over after that. I’d lie beside him at night listening to his breathing and wishing it would stop. I felt banished from the regular, warm, disheveled life other people led and bitterly alone. But over the years, these feelings faded. I drew away from him. I continued to make his dinners and iron his shirts; we were polite to each other; but I developed friends, activities, and a life of my own.

I’m not sure why I continued to share a bed with George, the bed where I sit beside his body now. There was not even a shadow of desire left between us. We didn’t hold each other for comfort in the dark as we aged, month by month and year by year, silently contemplating our final days and wondering which of us would die first, George with his unreliable heart, I with my diabetes and fragile bones.

I pull in a deep breath and turn to look at him. Oddly, George got better looking as he aged. By the time he was seventy he was gaunt, majestic even. That great beaked nose of his—my schnozz, he called it proudly—became more prominent, and the light in his eyes retreated under the white, waving weeds of his eyebrows, becoming milder and more diffuse. The mouth that had once looked petulant now seemed to be closed on some immutable truth.

We grew old together. We sagged. Our bowels clogged. When you’ve been married for decades you know everything about your partner, every facial expression and variation in vocal tone, the meaning of each and every intake of breath. And yet you don’t.

I never understood George, but there was a dialogue going on during those silent years all the same, beneath our daily activities, his body speaking to mine and mine to his, the way we conformed to each other at night, one turning as the other turned, both making a thousand minor adjustments even while the gap between us remained constant. When he was away at a conference, he was still in the house with me, his smell lingering in the armchair, saturating the clothes in the hamper. The edges of the book are blurry and worn. When you look closely, you can see what looks like an upside-down heart against the page, the muted color of old blood. Against the murk, the knives are startlingly bright, but they, too, are beginning to fade, blade dissolving against blood, blood softening blade, until you almost can’t tell one from the other.

I bend to kiss your forehead. It’s so cold it burns. You are not you any longer, George, Gyorgy, your urgency transmuted into stillness, your flesh into marble. You are finally dead, my old tyrant. And now the pain begins.

Juliet, thank you for this stunningly written, deeply heartbreaking story. I cried through it, although tears come easily this week for reasons we share. I'm as heartbroken as you at the "heinous genocide of its own." As painful and inexplicable as it is, I appreciate your speaking of it.

This one will stay with me. A fierce little story that resonates long and far. Thank you!